Brought to you by ARBICO Organics

These invasive insects were first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014. It is believed that they were stowaways on a shipment of imported stone. Spotted lanternflies (SLF) are exceptional stowaways/hitchhikers, and it is precisely this type of behavior that accounts for their rapid spread in states along the eastern coast of the United States. At the time of this writing (May 2023), they are found in Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia. Many experts believe that that number will climb within the next year to include states further south along the coast. By 2050 they are expected to be established all the way to California.

Spotted Lanternflies, despite their name, are not flies – they are True Bugs from the order Hemiptera. Hemiptera have sucking mouth parts, called proboscis, which work like straws. They use their proboscis to pierce into plant parts and suck out the sap. Some of the most damaging and challenging to control insects are from this order, like aphids, bed bugs, brown marmorated stink bugs and scale insects.

According to Cornell University, SLF have yet to cause significant damage to agricultural crops. The exception to this is grapes, where they have proven to be a serious problem. SLF are swarm feeders, and they can quickly overrun an orchard with hundreds of individuals on each vine. This will debilitate the vine, weakening it to the point that it produces poor or no blooms and fruit and loses its winter hardiness. These effects, as well as oozing, wilting and defoliation, can occur on any plant that SLF feeds on. Plants are often unable to withstand the swarm and simply die. Watch them flying through a vineyard here.

Since SLF do not sting or bite, they pose no direct risk to people. However, they do create significant trouble due to the copious amounts of sugary waste (known as honeydew), that they create. Some people report allergic reactions to honeydew, but this is not common. Mostly, it’s an unpleasant nuisance for people. It sticks on outdoor surfaces like porches, cars, benches and on clothing and pets. Honeydew also has an odor like fermentation that is unpleasant to most people but irresistible to many unwanted insects like ants and wasps. Bees are also drawn to it – they like to feed on the honeydew, especially when it is found on a Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) – the preferred host of SLF, and another invasive species. Apparently, it creates a uniquely tasty honey for an interesting reason. Read more here.

A significant issue with SLF is sooty mold. This fungus uses the honeydew as a grow medium and will quickly spread throughout the affected plant. Sooty mold spores and pieces of mycelia can be easily spread to other plants as well by splashing water or wind. Once there, the mold will exploit any weakness it finds to establish a foothold. More on sooty mold here.

So why is SLF so hard to control? Here are some reasons:

They are such skilled stowaways that their most-used method of getting around is through human activity. They will jump into carts, fly into trucks, attach themselves to bags, hide in clothing – they’ll hide pretty much anywhere but in water.

SLF are extremely mobile. As nymphs and adults, they are impressive jumpers. As adults they will fly short distances. They have been known to travel miles on their own by a combination of jumping, flying and walking. When you add their hitchhiking into the mix, it explains why they are spreading so quickly.

The needs of the swarm drive their behavior. Their mobility is necessary to meet the needs of all the members of the swarm, so they will move often to feed and affect new plants with each move. The swarm protects itself by quickly vacating an area that’s being sprayed and often it will return when the spray dissipates.

Their egg masses are hidden in plain sight. SLF females lay their eggs on all sorts of outdoor surfaces and items that are left outside (barbecue grills, folding chairs, etc.). She covers her eggs with a substance that’s white at first, but eventually it turns tannish-brown and cracks a bit. They look just like smears of dried mud, unremarkable and unnoticed.

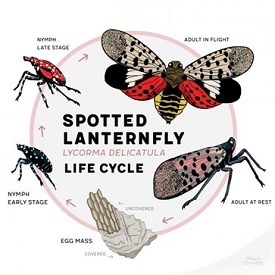

To get a grip on these wily insects, it takes a multi-pronged, diligent effort that addresses each life stage. SLF produces one generation a year, which includes an overwintering egg stage, four nymphal stages (instars) and an adult stage (more here). Egg cases need to be scraped off any surface they are found on and disposed of in such a way that they cannot survive. This can be done by putting them into a plastic bag filled with hand sanitizer or spraying them with a suffocant like dormant oil. In the other stages, trunk, branch, and foliar sprays will work to some extent but will probably need to be reapplied aggressively. Sticky traps and tree bands will keep some off foliage but must be monitored closely so that they do not fill up and become a bridge for other SLF. Neem oil, horticultural and dormant oils, insecticidal soaps and pyrethrins can be used as sprays. Fungicides as a pro-active pretreatment are a good idea, especially biologicals like Burkholderia spp. strain A396 and Beauveria bassiana.

At this point, SLF have become part of our pop culture. They have appeared on Saturday Night Live, which is the ultimate arbiter of pop culture. This article uses them as an insult (as in don’t be one) and there is no shortage of informational and creative ways to kill them online. Despite the entertainment value of these clips, it is important to remember that these are seriously invasive insects that the government is trying to control. If you come across them, they should be reported – here’s link that tells you how and here’s a link to some SLF Frequently Asked Questions.

Pam Couture is the Lead Content Writer at ARBICO Organics. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she is surrounded by family, friends, and nature. ARBICO Organics can be contacted at 800.827.2847 and you can visit their website at ARBICO-Organics.com.

Comment here